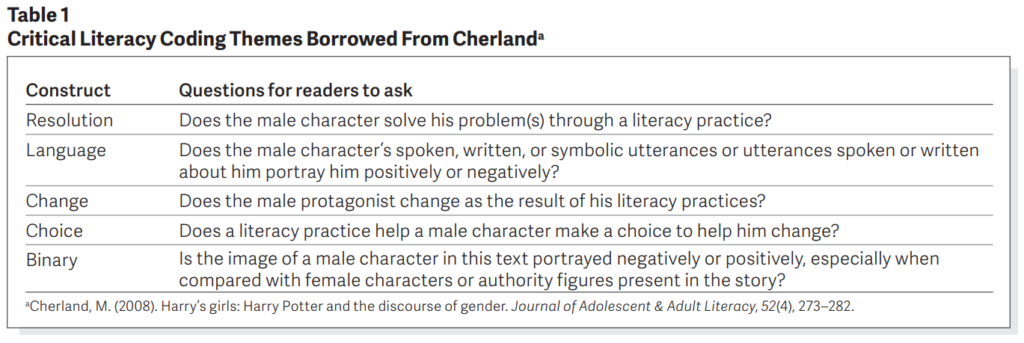

Literacy practices are not neutral activities. As children are taught to read, they learn to read the worlds they are introduced to as readers as they encounter gendered archetypes and identities (Giroux, 1997). We connected two literary frameworks to engage in a critical content analysis of male protagonists’ literacy practices in the earliest books that children read: Cherland’s (2008) applications of feminist poststructuralist theory and Zambo’s (2007) archetypes of male readers. Feminist poststructuralist theory outlined by Cherland (2008) provided tools of language for readers to identify and challenge gender binaries of male and female. Cherland observed that when readers make sense of the world in terms of two static gender roles, they preserve existing social hierarchies and oversimplifications that turn into common sense about what it means to be male or female. Borrowing from Cherland, we determined that five prompts can help readers better understand how male literacy practices are depicted in select picture books:

- How a problem is resolved with the aid of literacy for male protagonists

- How language is used when describing the male protagonist throughout the story

- How protagonists change as the text progresses and whether change is spurred through literacy

- How protagonist choices are made possible through language

- Whether gender binaries in words or illustrations are present or absent when a male protagonist is compared with female or authority figures in the same story

Ultimately, we wanted to know whether and how male protagonists used literacy practices to better their lives. Specifically, we wanted to know whether male protagonists solved their problems through literacy and became more powerful active agents of change in their own story lines. We borrowed our concept of language from Cherland (2008), who defined language as “the site where reality and the social order are created, constituted, and constructed”; it “shifts according to social context” (p. 275). Discourse of characters or about characters represents “patterns of public and private language that reflect and also construct patterns of meaning” (p. 275). We determined that language could be spoken or written or might include symbolic communication that helps readers determine what kind of character a male protagonist became during the plot of a text.

We wanted to track whether and how male characters changed as a result of their literacy practices and whether they became multidimensional characters capable of change rather than flat characters who do not experience epiphanies. We wanted to determine whether and how young males made choices with literacy that were tools of this change. Finally, we wanted to observe how language, change, and choice worked together to create identity construction for young male characters. (See Table 1 for definitions of these constructs, which became part of our coding themes.)

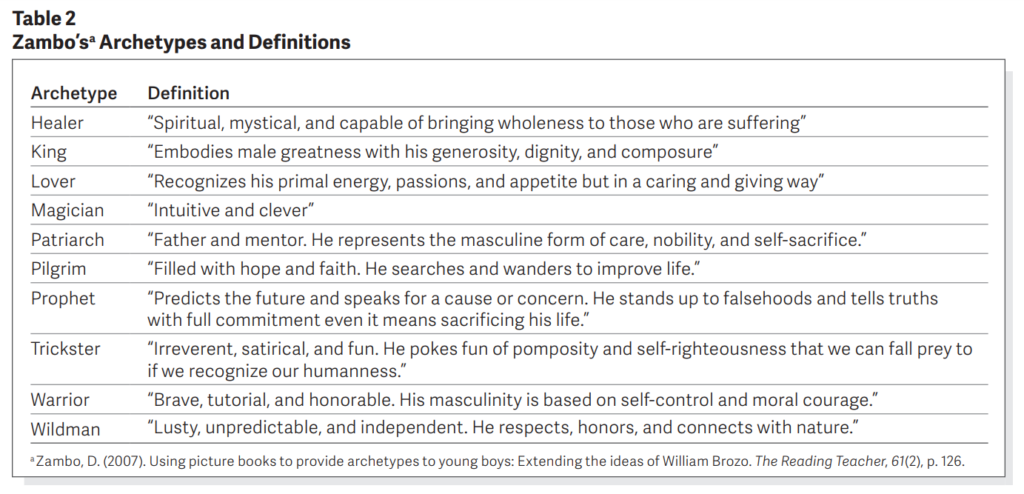

Zambo (2007) observed that picture books may offer young readers portrayals of engaged male readers and writers and that these books can be important tools to demonstrate to young males that literacy is valuable and identity-enhancing. Noting that honorable archetypes of manhood are consistent across cultures, Zambo offered 10 male archetypes that young boys can use to discuss masculinity in picture books: Healer, King, Lover, Magician, Patriarch, Pilgrim, Prophet, Trickster, Warrior, and Wildman (see Table 2 for descriptions of these archetypes). She asserted that “literature with archetypes motivates boys to read because it appeals to their psyche and connects to their lives, their interests, and their needs” (Zambo, 2007, p. 124). We applied and extended Zambo’s archetypes as we analyzed the literacy practices of male protagonists in recent picture books that children have designated as excellent.

Research Methods

To answer our research question, we employed the methodology of critical content analysis (Beach et al., 2009) as it is a good fit for examining and interpreting written artifacts (White & Marsh, 2006). In conducting a content analysis, we coded and identified themes and patterns in 21 recent (2000–2014) Children’s Choices picture books according to literacy markers of male protagonists in these books that match Butler’s (1990) definition of gender. Whenever a male protagonist was involved in an act of symbolic communication, such as reading, writing, creating art, or dancing, or was placed in a setting with tools of symbolic communication such as books, art tools, or drawings in illustrations or text, we documented that marker of literacy. After we closely read each text, at least two readers noted the archetype that was presented for the male protagonists. When readers did not agree with an archetype, we discussed selection(s) until consensus was reached based on evidence.

After all of the authors read several Children’s Choices picture books, we had distinct impressions that differences in gendered literacy practices existed. We decided that we wanted our content analysis to be a critical analysis of how gender is portrayed using quantitative data that reading teachers and readers of picture books could replicate. Our study is “critical” because we employed both Zambo’s (2007) existing archetypes of boys and Cherland’s (2008) poststructuralist feminist theory in order “to think within, through, and beyond the text” (Beach et al., 2009, p. 130).

Table 3 lists our text set. The first 11 books were selected randomly from the lists of Children’s Choices picture books published between 2000 and 2014 in The Reading Teacher. We numbered every picture book for a particular year and, using a basic Internet tool to choose a number at random, selected one book to analyze for each of those years. Books 12–21 were selected purposefully from the years 2013 and 2014 based on summaries of plot lines emphasizing literacy in Children’s Choices picture books. The selected texts were chosen because their male protagonists were included in summaries and because they had settings apparent on covers or in summaries that were likely to be rich in literacy production or literacy markers.