A local professional artist stands in front of a group of students in a high school English language arts classroom.

“Images are texts in the big sense of the word,” he begins. “Texts communicate, share ideas, and make connections.”

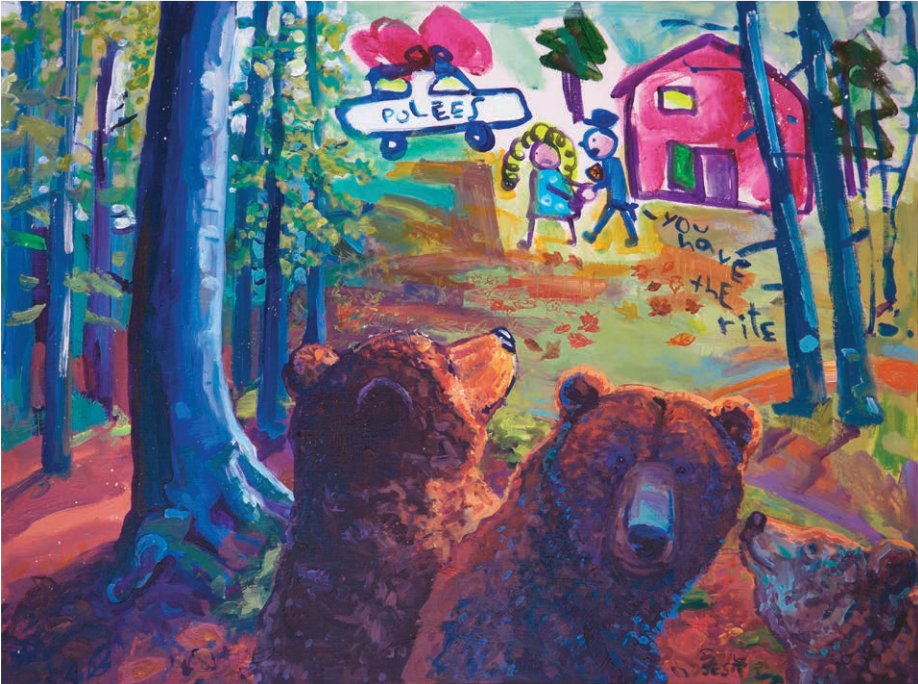

He pauses. “Let’s read some images together.” On the white board behind him, he shows examples of his own artwork. “What’s the story with this text?” he asks about the first piece displayed on the board (Figure 1). “What details do you notice? What choices did I make as an artist in order to communicate something?” Students offer various responses and enjoy trying to figure out the play on words in the painting. “The choices you make as an artist matter,” the artist continues. “But how do we make these choices?”

The artist visit is part of a local school’s involvement in an annual month-long community-wide reading program focused on the reading of one book. As program director of the reading program and English education professor at a liberal arts college, I allocate funds to hire local professional artists to collaborate with area teachers and students in creating visual art responses to the selected piece of literature. In the past four years, over 40 teachers have participated in the reading program, many of whom, like Beth Mawdsley Sherwood, the co-author of this series of articles, have participated multiple times. The student–artist collaboration begins at least one month in advance of the program and cumulates with the program’s closing event, the Student Exhibition of Learning, in which collaborative and individual student art is shared with the community. One thousand people—teachers, students and their families, and community members—attend this event.

In this article, we reflect on our experiences of integrating visual arts, specifically painting, into an English language arts curriculum. Although each of us had previously used art as a response to literature with our students, neither of us had before collaborated with professional artists or been as intentional about scaffolding students into the processes of researching, practicing, and producing art. Our explorations with this have led to our “co-equal arts integration” framework, which considers the purposes and processes of visual arts integration by exploring ways that efferent and aesthetic responses to literature, the artistic process and the final product, and personal and communal audiences can be addressed in generative ways in the English language arts classroom.

The pressures of an already packed curriculum, lack of funding, scheduling logistics, and feelings of “artistic” inadequacy are valid reasons for not integrating the visual arts into English language arts classrooms and we can speak firsthand to many of these reasons. Our adventures in arts integration these past four years, however, have taught us that there are creative ways to respond to these potential road blocks and that the benefits of doing so are significant and compelling. As is well documented in the field, arts integration has the potential to diversify instruction, increase student engagement and investment, encourage students to make metaphoric connections, become detail-oriented in texts, problem solve, and work collaboratively (Defauw & Taylor, 2015; Eisenkraft, 1999; Holdren, 2012; Taylor, Carpenter, Ballengee-Morris, & Sessions, 2006; Whitelaw & Wolt, 2001). More recent scholarship has highlighted the power of community-based practices in art education and the ways art integration can connect social and cultural gaps through the collaborations of community artists and educators (Woywod & Deal, 2016).

In our other “Arts Integration” articles, we use our “co-equal arts integration” framework to explore different ways to approach visual arts integration in the English language arts classroom. We borrow this term, “co-equal,” from Bresler’s (1995) articulation of four ways to incorporate arts into classrooms. These include social integration— when art is used for school social events; affective—when art is used to help students to express themselves; subservient—when art is used to “spice” up other subjects such as craft-based activities that do not push the boundaries of basic cognitive thinking; and co-equal—when specific art skills are incorporated into different subject areas alongside of competencies within those disciplines. We expand Bresler’s use of “co-equal” to address the many ways educators can integrate visual arts in response to literature in nonbinary ways. It is our hope that art educators and others might find our framework helpful in envisioning and implementing arts integration in their own contexts.

Arts Integration Articles:

- Emphasizing Process and Product

- Encouraging Efferent and Aesthetic Responses to Literature

- Creating Space for Personal and Community Audiences

References:

Bresler, L. (1995). The subservient, co-equal, affective, and social integration styles and their implications for the arts. Arts Education Policy Review, 96(5), 31-37.

Defauw, D. L., & Taylor, J. A. (2015). Art and culture in the English language arts: Research findings and educators’ perspectives. Journal of Reading Education, 40(2), 3-12.

Eisenkraft, S. L. (1999). A gallery of visual responses: Artwork in the literature classroom. English Journal, 88(4), 95-102.

Holdren, T. S. (2012). Using art to assess reading comprehension and critical thinking in adolescents. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 55(8), 692-703.

Taylor, P., Carpenter, B. S., BallengeeMorris, C., & Sessions, B. (2006). Interdisciplinary approaches to teaching art in high school. Reston, VA: National Art Education Association.

Whitelaw, J., & Wolt, S. A. (2001). Learning to “see beyond”: Sixthgrade students’ artistic perceptions of The Giver. The New Advocate, 14(1), 57-67.

Woywod, C., & Deal, R. (2016). Art that makes communities strong: Transformative partnerships with community artists in K–12 settings. Art Education, 69(2), 43-51.